The Pentagon is Preaching

The Department of War has begun posting Bible verses alongside military drills.

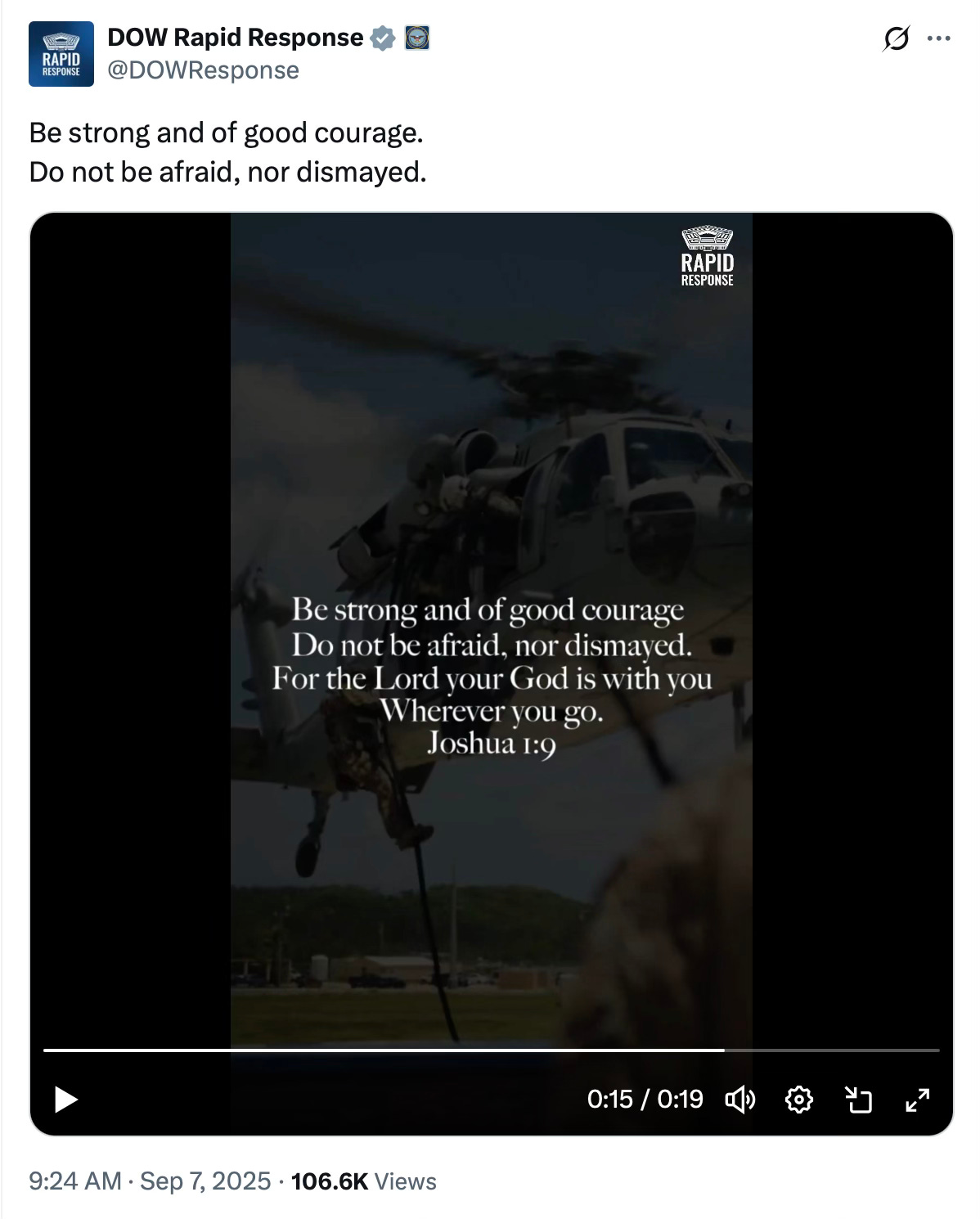

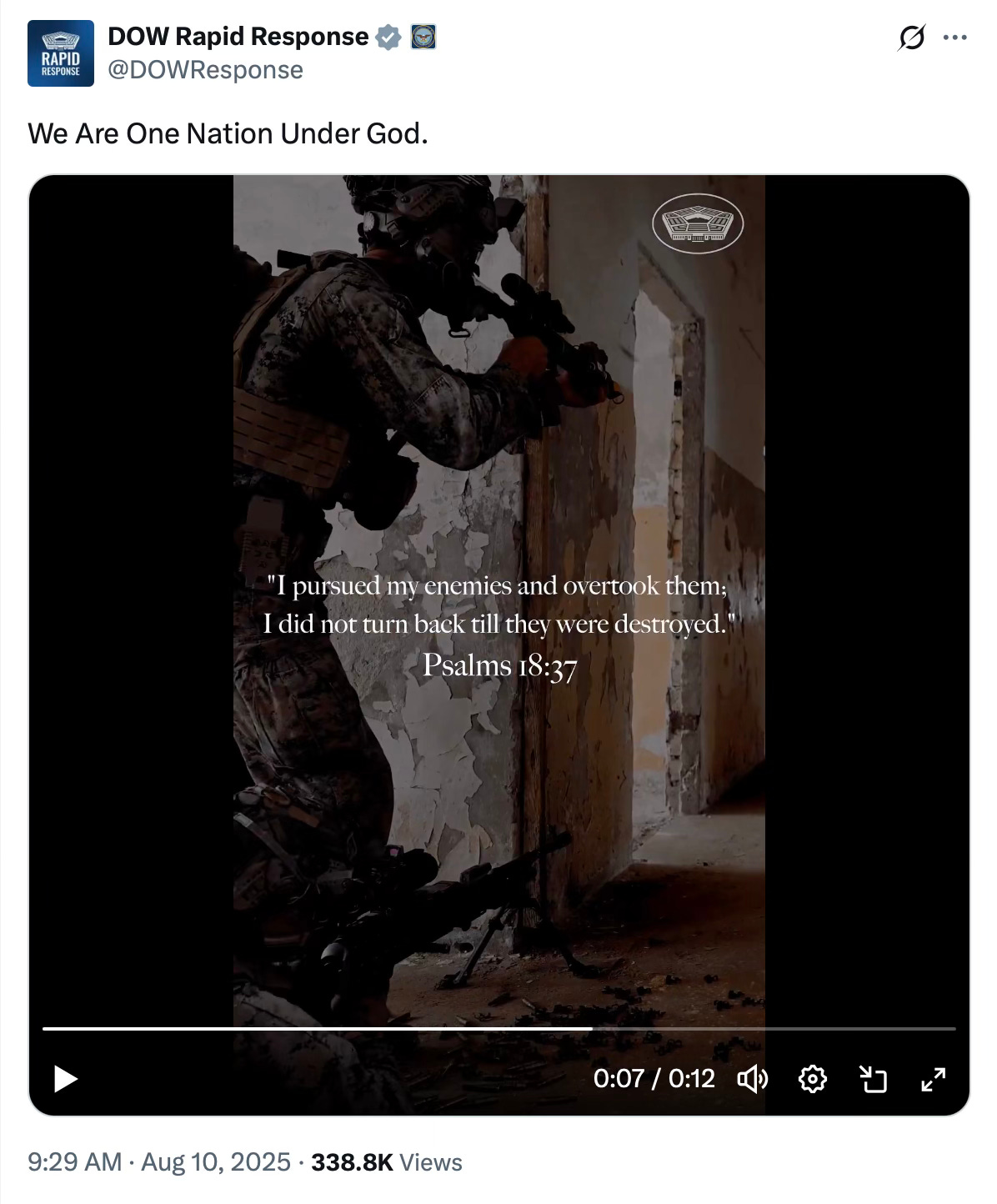

On September 7, the War Department’s rapid-response account pushed a 19-second clip of soldiers running drills and aircraft banking, overlaid with words from Joshua: “Be strong and of good courage … for the Lord your God is with you” (Josh 1:9). A month earlier on August 10, another clip used a conquest line from the Psalms: “I pursued my enemies and overtook them” (Ps 18:37). Reporting in Religion News Service described the posts in sober tones, noting that some link them to Christian nationalism, and quoted experts warning about the merger of scripture and state power (André, 2025).

Baptist scholar Brian Kaylor stressed that these verses were originally directed to “marginalized people under attack, not imperial armies.” To lift them out of context and stamp them on military imagery, he said, is a selective literalism that “turns scripture into a warrant for force.” Michael Weinstein of the Military Religious Freedom Foundation raised a related concern: using Bible verses in official channels “privileges one faith” and risks damaging “the cohesion and trust” of a pluralist military (André, 2025).

Civil religion or Christian nationalism?

There is an important distinction here. In his classic essay Civil Religion in America, Robert Bellah argued that the United States has long had a public religious grammar, a set of beliefs, symbols, and rituals that is neither sectarian nor in any specific sense Christian. Civil religion lets presidents invoke God in a way meant to bind a diverse people to moral purposes (Bellah, 1967). Bellah emphasized a division of labor. Churches do not control the state, the state does not control the churches, and officials operate within a broad, non-sectarian grammar rather than a denominational creed.

The War Department’s videos do not fall into that category. They are not metaphorical invocations of blessing. They are literal proof-texts superimposed on weapons and maneuvers. Comparative work on sacralized politics flags this as the sacralization of state violence, the shift from moral language to religious warrant for coercive power (Rouhana & Shalhoub-Kevorkian, 2021).

This is not a new temptation. Bellah himself warned that the “American Israel” theme, the idea of America as a chosen nation, has often been used to legitimate imperial adventures and to consecrate conflict through the language of sacrifice. That language is embedded in the civic calendar through Memorial Day and national cemeteries (Bellah, 1967). Feminist theologian Kelly Denton-Borhaug later traced how U.S. officials, especially after 9/11, mobilized sacrifice language to sanctify war, converting military loss into a quasi-sacrament that renders dissent morally suspect (Denton-Borhaug, 2007).

The War Department videos sit squarely in that trajectory, but with an additional twist. They do not only memorialize loss or invoke unity. They overlay conquest texts directly onto images of combat. That is not civil religion. It is Christian nationalism.

Why this messaging matters

Population-level data help calibrate the stakes. PRRI’s 2024 American Values Survey shows the divide is sharp. Seven in ten Americans say the country is headed in the wrong direction, with nearly all Republicans (94 percent) taking that view compared to four in ten Democrats (41 percent). Republicans are far more likely than Democrats to believe American culture has changed for the worse since the 1950s (68 percent vs. 31 percent). The gap extends to questions of democracy and violence. Nearly one in five Republicans (19 percent) said Trump should declare the 2024 election invalid and do whatever it takes to assume office if he loses. Almost three in ten Republicans (29 percent) agreed that “true American patriots may have to resort to violence to save the country.” By comparison, only 8 percent of Democrats agreed with that statement (Public Religion Research Institute, 2024).

Peer-reviewed studies trace the consequences. In Politics & Religion, Samuel Perry and Joseph Grubbs show that Christian nationalism predicts support for leaders who suspend democratic norms during national emergencies—especially when people feel their in-group power is threatened (Perry & Grubbs, 2024). In Political Behavior, Miles Armaly, David Buckley, and Adam Enders demonstrate that Christian nationalism, especially when fused with victimhood, racial identity, and conspiracism, predicts support for political violence, including justification of the January 6 attacks (Armaly, Buckley & Enders, 2022).

The official social media channels posting videos of scripture-over-war-footage is not a morale boost. In a country where millions already see politics through a Christian-national lens, these cues correlate with greater tolerance for democratic shortcuts and violence. That is why the distinction between civil religion and Christian nationalism is not academic hairsplitting. It is a democratic tripwire.

Personnel is policy

Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth has cultivated a crusader image, from the Deus Vult tattoo on his arm to speeches calling for an “American Crusade” to defend Western civilization. Reporting by Mike Baker and Ruth Graham documented those details in depth. When communications produced under his leadership overlay conquest verses on combat imagery, it looks less like a rogue social media post and more like a coherent project.

DHS and ICE as a mirror

The same trend appears across the Trump administration. Department of Homeland Security and Immigration and Customs Enforcement feeds have been filled with videos and memes that borrow both biblical and pop culture references. Washington Post columnist Carolina Miranda describes one clip set to the verse from Isaiah, “Here am I. Send me,” paired with tactical raids and helicopters. Another cites Proverbs, “The wicked flee when no man pursueth; but the righteous are as bold as a lion,” intercut with dialogue from The Batman (Miranda, 2025). The effect is a holy-war narrative where agents are cast as God’s soldiers against shadowy enemies.

The imagery does not stop there. ICE social media has borrowed Manifest Destiny art, slogans like “Which way, American man,” and even Bible verses to frame immigration enforcement as a spiritual crusade. As Gorski and Perry note, Christian nationalism always needs an enemy, whether Native Americans, Catholics, immigrants, or the political left. The enemy shifts, but the us-versus-them logic remains (Gorski & Perry, 2022).

A test for pluralism

One way to measure this is to flip the script. If identical clips were released with Qur’anic verses instead of biblical ones, how would they land? Most Americans would quickly recognize that as the state privileging one faith and redrawing boundaries of belonging. Comparative research on sacralized politics finds that this is what happens when religious claims fuse with national power. They draw hard insider and outsider lines and legitimize demonization (Rouhana & Shalhoub-Kevorkian, 2021). Inside a pluralist military, those lines shape not just public opinion but the culture of the ranks.

Resisting this drift does not mean banishing religion from public life. It means insisting that biblical language in official communications serve universal purposes such as mourning the dead, binding wounds, and setting moral horizons. It means distinguishing chaplaincy, which cares for service members of all faiths, from messaging that brands the state with conquest texts.

The War Department and DHS examples reveal a consistent logic. America is cast as chosen, under siege, and authorized to fight. That is not civil religion. It is Christian nationalism, and it is being carried by the official voice of the state.

Further Reading

André, F. (2025, September 9). Department of War quotes Bible in apparent embrace of Christian nationalism on social media. Religion News Service. https://religionnews.com/2025/09/09/department-of-war-quotes-bible-in-apparent-embrace-of-christian-nationalism-on-social-media/

Armaly, M. T., Buckley, D. T., & Enders, A. M. (2022). Christian nationalism and political violence: Victimhood, racial identity, conspiracy, and support for the Capitol attacks. Political Behavior, 44(3), 937–960. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-021-09758-y

Bellah, R. N. (2005). Civil religion in America. Daedalus, 134(4), 40–55. (Original work published 1967). https://www.jstor.org/stable/20027022

Denton-Borhaug, K. (2007). The Language of “Sacrifice” in the Buildup to War: A Feminist Rhetorical and Theological Analysis. The Journal of Religion and Popular Culture, 15(1), 2-2. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A167897642/AONE?u=creighton&sid=googleScholar&xid=c692c9a8

Gorski, P. S., & Perry, S. L. (2022). The flag and the cross: White Christian nationalism and the threat to American democracy. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780197618684.001.0001

Miranda, C. A. (2025, August 26). Preposterous ICE videos have a holy war to sell you. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2025/08/26/dhs-social-media-religious-imagery-battle/

Perry, S. L., & Grubbs, J. B. (2024). Christian nationalism and support for leaders violating democratic norms during national emergencies. Politics & Religion, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755048324000208

Public Religion Research Institute. (2024). Findings from the 2024 American Values Survey: Executive summary. https://prri.org/american-values-survey/

Rouhana, N. N., & Shalhoub-Kevorkian, N. (Eds.). (2021). When politics are sacralized: Comparative perspectives on religious claims and nationalisms. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108768191