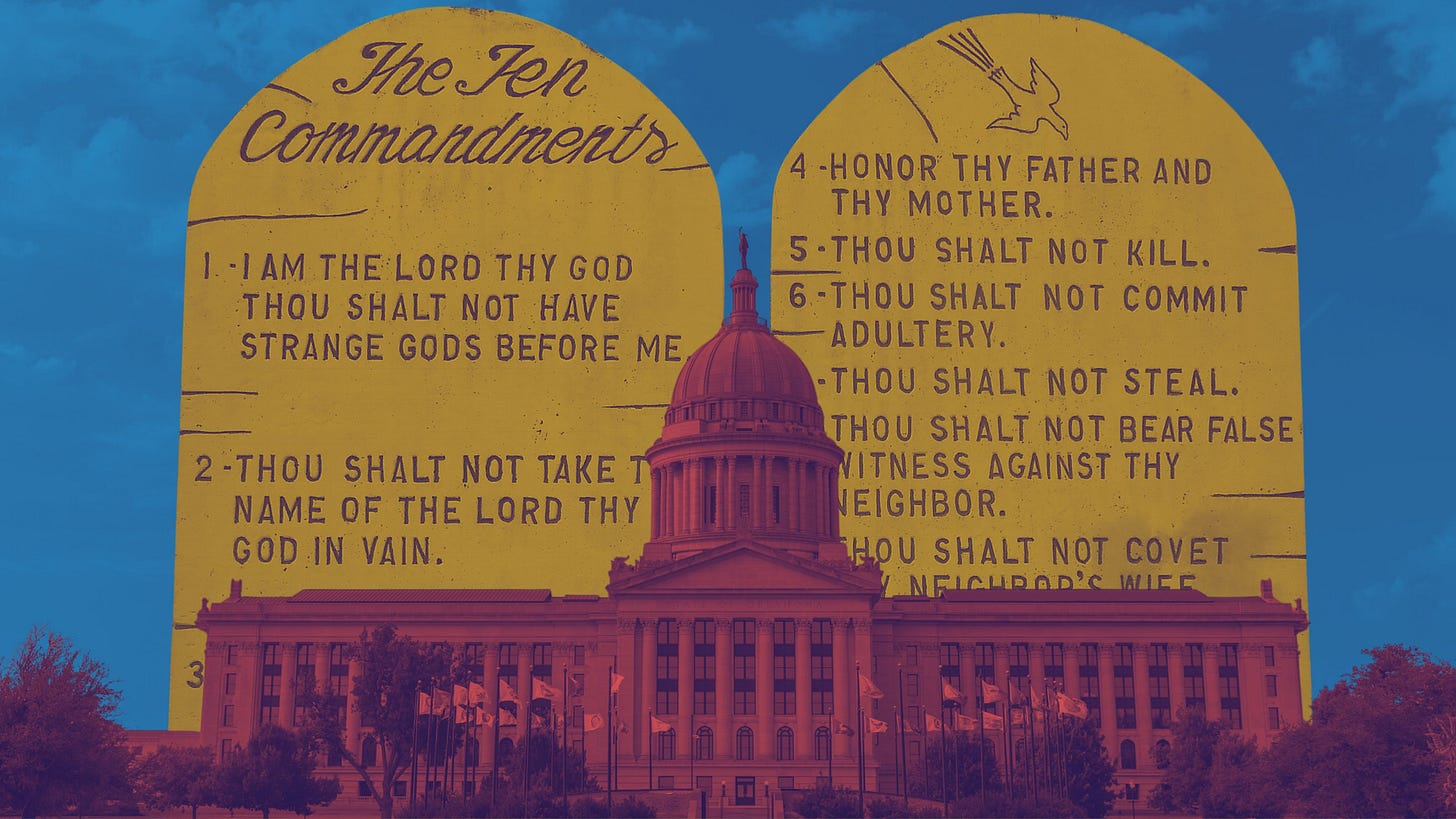

Oklahoma is Writing a Lesson Plan for Christian Nationalism

How Oklahoma is rewriting public education—and what it means for the rest of us.

Oklahoma’s top education official isn’t just rewriting the curriculum, he’s rewriting the boundaries between church and state.

I have been following Oklahoma for months because it offers a clear view of how an ideology moves from rhetoric to policy. The pattern is not subtle. State Superintendent Ryan Walters directed schools to incorporate the Bible in grades 5 through 12, warning of consequences for districts that did not comply. He issued a request for proposals for Bibles and Bible-led instructional materials, actions that were paused by the Oklahoma Supreme Court in March 2025.

The same office advanced new social studies standards that instruct students to look for discrepancies in the 2020 election. These curriculum changes incorporate debunked claims as subject for classroom analysis, and have faced immediate backlash from educators and lawmakers.

There is a broader agenda at play. An attempt to establish the nation’s first publicly funded religious charter school, St. Isidore of Seville Catholic Virtual School, was blocked. The U.S. Supreme Court ended in a 4–4 tie in May 2025, which left intact a lower court ruling against it while not setting a national precedent.

Walters also tried to normalize school-sponsored devotion. In November 2024, he directed districts to show students a video in which he announced a new department of religious freedom and patriotism and invited them to join him in prayer for Donald Trump. School districts pushed back, and the state attorney general said Walters lacked authority to make it mandatory.

I read these developments alongside scholarship on Christian nationalism, which shows that higher levels of Christian nationalist sentiment strongly correlate with support for privileging Christianity in public life even when it undermines pluralism.

In Oklahoma, the political structure helps explain how these policies advance with limited institutional resistance. The state has a Republican trifecta and veto-proof supermajorities in both legislative chambers, lowering the political cost of testing constitutional boundaries which we see in these initiatives.

There is also a cultural dynamic at work. Many people of faith are uncomfortable pushing back against policies presented as “religious freedom,” even when they apply only to one faith tradition. The Bible is framed as cultural heritage, with no parallel inclusion of the Quran, Torah, Bhagavad Gita, or sacred texts of other faiths. This is not pluralism: it’s preference under the guise of civics, reinforced through legal and social pressure.

So I keep returning to these urgent questions:

What does this mean for the country? States borrow. If Bible mandates, prayer videos, and election-doubt standards survive in one state, they will travel, adapted and repackaged in other conservative-controlled legislatures.

What does this mean for Christians who see these moves as unpatriotic or unchristian? Many feel silenced and reluctant to oppose policies that claim religious legitimacy. That silence cedes ground to ideological takeover. It is politically convenient for many who subscribe to conservative theology, whether Catholic, non-denominational, or Protestant, because the framing makes opposition feel like betrayal. Education policy is presented as part of a cosmic struggle. Leaders draw on imagery from Revelation, speak of battles against principalities and demonic forces, and portray their opponents as agents of evil.

This framing changes the nature of the debate. A disagreement over curriculum becomes a test of spiritual fidelity. Believers are told they are living in the Acts of the Apostles or standing on the front lines of a holy war. It creates a sense of urgency and excitement, as if every school board meeting is another step in a sacred mission. Samuel Perry’s research shows that Christian nationalism thrives when political identity is fused with religious purpose, especially when leaders frame their cause as divinely mandated. When the stakes are cast in these terms, compromise looks like surrender and neutrality is treated as complicity. In that environment, resisting the agenda is not just politically risky, it is framed as spiritually dangerous.

What happens to the church when faith becomes indistinguishable from a partisan political project? What does this mean for pluralism in the Trump era? The Supreme Court’s tie over the charter school case bought time, not resolution. Litigation and political maneuvering will continue in classrooms, governance structures, and funding mechanisms. The stakes are public education and civic equality.

This newsletter begins here because Oklahoma is a laboratory. I will trace these policies, the networks spreading them, and the research decoding them. Clarity and evidence are our tools. If we notice the pattern early, we can question it with precision and choose a different path for our schools and our country.

Further Reading

If you want to see the reporting and public records that informed this post, these articles and rulings offer essential context. They cover the Bible mandate, curriculum changes, legal fights over religious charter schools, and the broader political strategies at play in Oklahoma.